Deadheading, or the practice of removing spent flowers, is often promoted as a way to keep gardens neat and encourage new blooms.

While this works wonderfully for annuals like zinnias or geraniums, some plants benefit more when you leave their fading flowers, seed pods, or hips intact.

For these plants, deadheading can actually reduce their impact – removing seeds that could self-sow, cutting off food for birds and pollinators, or eliminating striking seed heads that give your garden four-season beauty.

Here are 15 flowers you shouldn’t deadhead – and why resisting the urge to snip those spent blooms can make your garden healthier, wilder, and more beautiful year after year.

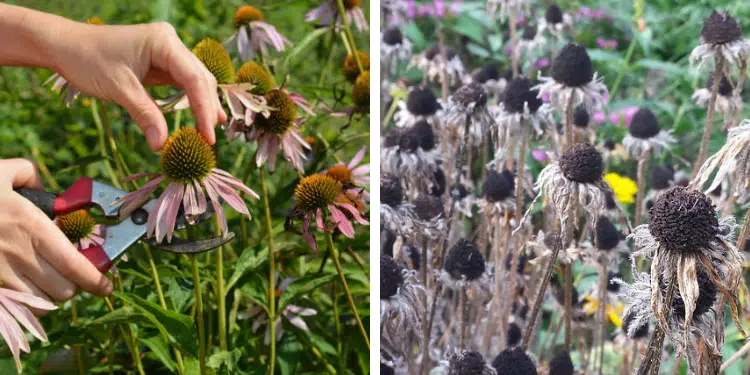

1. Coneflowers (Echinacea)

Coneflowers are one of the most iconic perennials in cottage gardens. Their daisy-like petals fade into large, spiky seed heads that persist into fall and winter.

- Why not to deadhead: Those seed heads are beloved by goldfinches and chickadees. They also add striking structure when capped with frost or snow.

- Bloom cycle: Summer through fall. Plants may rebloom lightly if deadheaded early, but leaving the last flush to set seed is best.

- Wildlife value: Provides both food (seeds) and shelter for birds.

- When to prune: Cut back in early spring before new growth emerges.

2. Black-Eyed Susans (Rudbeckia)

These cheerful yellow flowers light up borders from midsummer into fall.

- Why not to deadhead: Their dark, cone-shaped centers are seed buffets for birds, particularly finches.

- Bloom cycle: July–September.

- Wildlife value: Seeds feed birds, while the flowers attract bees and butterflies.

- When to prune: Allow stalks to remain through winter, then trim back in early spring.

3. Sunflowers (Helianthus)

Sunflowers are summer icons that continue to give long after their petals fade.

- Why not to deadhead: Their seed heads are valuable food for birds, squirrels, and even overwintering insects.

- Bloom cycle: Mid to late summer, depending on variety.

- Wildlife value: Nectar for pollinators while in bloom; protein-packed seeds for birds in fall.

- When to prune: Leave standing until winter storms knock them down, then compost the stalks or leave them for wildlife shelter.

4. Ornamental Grasses

Though technically not flowers, ornamental grasses produce seed plumes that shine in the garden.

- Why not to deadhead: Their airy plumes add height, texture, and winter motion. Birds use the seed heads for food and shelter.

- Bloom cycle: Late summer into fall.

- Wildlife value: Seeds and cover for overwintering species.

- When to prune: Cut back hard in late winter or early spring before new shoots appear.

5. Sedum (Stonecrop, especially Autumn Joy)

Sedum produces clusters of starry blooms that turn bronze as they fade.

- Why not to deadhead: The dried flower heads look like sculptures, especially dusted with frost.

- Bloom cycle: Late summer through fall.

- Wildlife value: Nectar for late pollinators; seed heads provide structure.

- When to prune: Remove old stems in spring as new green shoots emerge from the base.

6. Globe Thistle (Echinops)

Known for their striking, spiny blue blooms, globe thistles remain impressive even as seed heads.

- Why not to deadhead: Their globe-like seed heads provide architectural winter interest and food for birds.

- Bloom cycle: Mid to late summer.

- Wildlife value: Attracts bees and butterflies during bloom, and birds later.

- When to prune: In spring, cut stalks down to the ground to make way for new growth.

7. Alliums (Ornamental Onions)

Alliums are beloved for their bold, spherical blooms.

- Why not to deadhead: Even after flowering, their dried seed heads resemble bursts of fireworks, making them highly ornamental.

- Bloom cycle: Late spring into early summer.

- Wildlife value: Pollinators adore their nectar; dried heads provide garden texture.

- When to prune: If reseeding is a problem, clip seed heads after they fade; otherwise, leave for ornament.

8. Clematis (Certain Varieties)

Some clematis, like C. tangutica, form whimsical, feathery seed heads.

- Why not to deadhead: Their silky tufts extend ornamental appeal long after flowering.

- Bloom cycle: Depends on variety – spring or summer bloomers.

- Wildlife value: Pollinator-friendly flowers; seed heads add ornamental value.

- When to prune: Follow specific clematis pruning group guidelines; don’t remove seed heads prematurely.

9. Milkweed (Asclepias)

A keystone plant for monarch butterflies, milkweed’s life cycle is tied to its pods.

- Why not to deadhead: The seed pods burst open to release silky parachutes that spread new plants. Deadheading prevents reseeding.

- Bloom cycle: Summer.

- Wildlife value: Host plant for monarch caterpillars and nectar for pollinators. Seeds provide natural propagation.

- When to prune: Remove only after seeds disperse in fall.

10. Columbine (Aquilegia)

Columbine’s nodding blooms are charming, but its seed pods are just as important.

- Why not to deadhead: They readily self-seed, providing new plants each year. Removing flowers stops this natural spread.

- Bloom cycle: Spring to early summer.

- Wildlife value: Hummingbirds love the flowers; seeds ensure longevity in the garden.

- When to prune: Allow seed pods to mature and drop before cutting back.

11. Lupines

Tall spires of lupines are early summer stars.

- Why not to deadhead: Their seed pods can help reseed, ensuring longevity. Some gardeners deadhead early blooms for a second flush, but later flowers should be left for seeds.

- Bloom cycle: Late spring to early summer.

- Wildlife value: Nectar for bees and butterflies; seeds add natural reseeding.

- When to prune: Deadhead selectively; allow late pods to ripen and fall naturally.

12. Bachelor’s Buttons (Cornflowers)

These annuals are champions at self-seeding.

- Why not to deadhead: Leaving some seed heads ensures next year’s display without replanting.

- Bloom cycle: Spring through midsummer.

- Wildlife value: Pollinator-friendly; seeds self-sow.

- When to prune: Pull spent plants in late summer once seeds have scattered.

13. Nasturtiums

Nasturtiums are edible and vibrant but also prolific reseeders.

- Why not to deadhead: Their seeds drop and sprout the following year, saving you from replanting.

- Bloom cycle: Summer to frost.

- Wildlife value: Nectar for pollinators; seed pods are edible for humans.

- When to prune: Collect some seeds for controlled planting but leave many to fall naturally.

14. Hollyhocks

Hollyhocks are tall, stately, and biennial – self-seeding is essential.

- Why not to deadhead: If you cut flowers too early, you won’t get seeds. Without reseeding, your hollyhocks may disappear after two years.

- Bloom cycle: Summer.

- Wildlife value: Pollinator magnet. Seeds ensure the next generation.

- When to prune: Allow pods to dry and scatter before trimming stalks.

15. Roses (Varieties with Hips)

Most roses benefit from deadheading – but not those grown for hips.

- Why not to deadhead: Rugosa and species roses produce hips – bright red or orange fruits – that are both beautiful and nutritious. Birds feast on them in winter, and humans can use them for teas and jams.

- Bloom cycle: Summer into fall.

- Wildlife value: Nectar for pollinators, hips for birds and mammals.

- When to prune: Leave hips to mature; prune back in late winter.

Why These Flowers Thrive Without Deadheading

Choosing not to deadhead these flowers supports:

- Self-seeding: Many of these plants naturally multiply when left alone.

- Wildlife habitat: Birds, bees, butterflies, and even beneficial insects rely on seeds and seed heads.

- Winter beauty: Frosted seed heads, stalks, and plumes add texture to dormant gardens.

- Low-maintenance gardening: Less pruning means less work for you.

Deadheading has its place, but knowing when not to deadhead is just as important.

By leaving seed heads on coneflowers, milkweed, hollyhocks, roses, and more, you’re not neglecting your garden – you’re enhancing its natural rhythm.